Weathering the Future

Agricultural climatologist Pam Knox helps connect science to everyday life for farmers and communities

By Maria M. Lameiras

Weathering the Future

Agricultural climatologist Pam Knox helps connect science to everyday life for farmers and communities

By Maria M. Lameiras

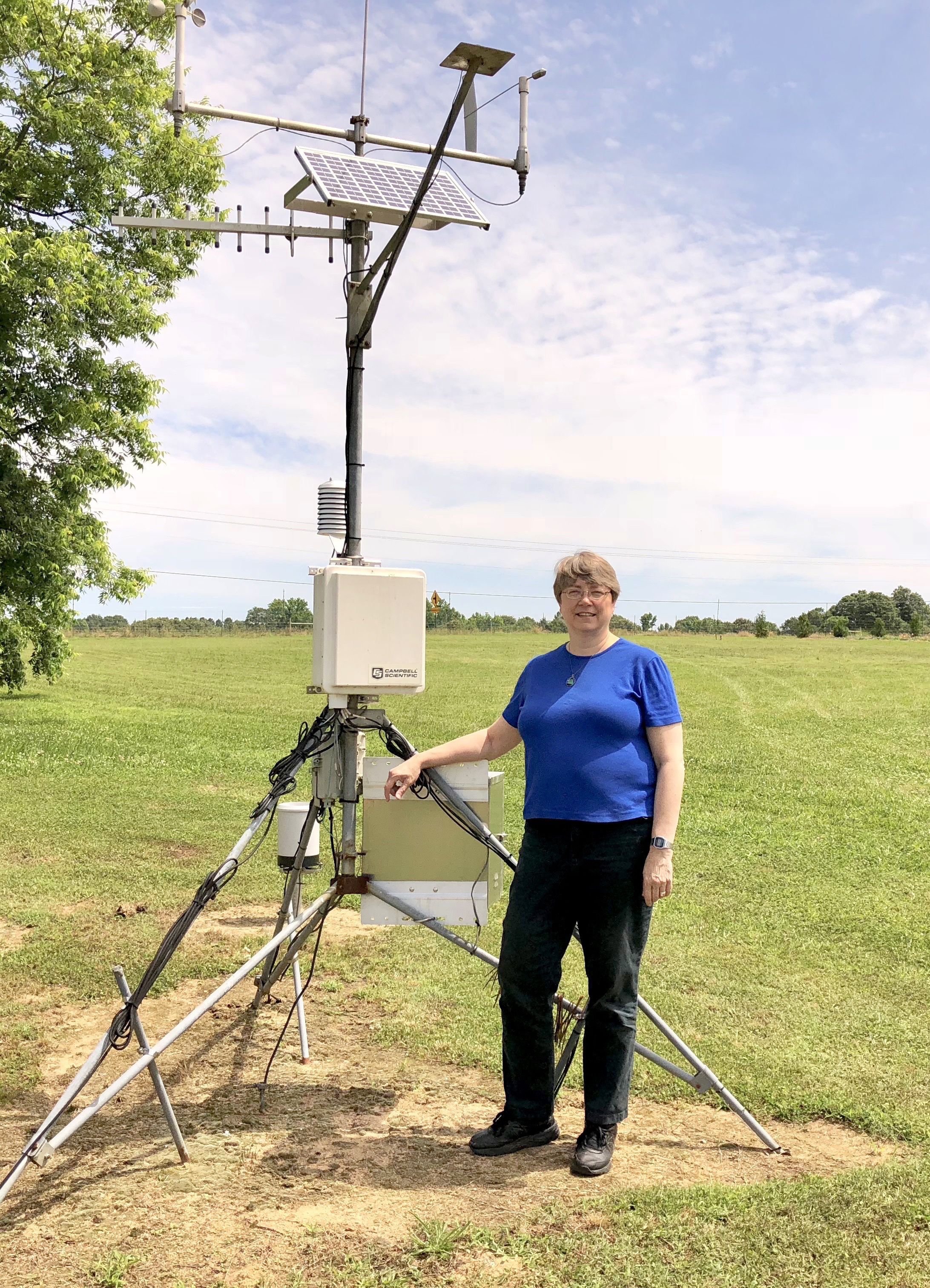

From her cozy office at the J. Phil Campbell Research and Education Center in Watkinsville, Georgia, Pam Knox has a clear view of the sky, and that is the way she likes it. In fact, she’s built a career on it.

“One of the nicest things about studying meteorology is I can look outside the window and understand what's going on in the atmosphere, what's causing the kinds of clouds we get, and where the rain is happening and where it's not,” said Knox, director of the University of Georgia Weather Network.

“What kind of cool job is that, right?”

A career built on curiosity

Like many meteorologists, Knox had a formative weather experience as a child.

“When I was at the third grade, a tornado touched down two blocks from my house, and that was unusual for that area, for Grand Rapids. It was April 21, 1967, a Friday night. It was already dark and pretty early in the severe weather season for Michigan,” said Knox, who was supposed to attend a church event that evening at the school where her father was principal.

“My friend was supposed to play a piano piece, so we were all excited about that. We got to the gym and started eating dinner, and that was when we had the tornado warning. They had just started the program, so my friend never got to play her piano piece because, you know, with a tornado, you don't want to have people in a big open space,” she recalled. “My dad was the principal, so my mom went into the school office, and she said she heard the tornado, you know, the freight train sound. I don't remember hearing it, but the tornado went between the school and our house.”

After the tornado passed, Knox remembers driving home in the dark after the power was knocked out.

“We lost most of the trees in our neighborhood and we didn't have power for a weekend. One of my friends’ garages was picked up, turned 90 degrees and set back down, so the garage door was opening into the yard,” Knox said. “I never thought about going into the weather for a career, but after that, of course I was interested in the weather. And I think it's a very typical story for meteorologists to have a big weather event.”

A career built on curiosity

Like many meteorologists, Knox had a formative weather experience as a child.

“When I was at the third grade, a tornado touched down two blocks from my house, and that was unusual for that area, for Grand Rapids. It was April 21, 1967, a Friday night. It was already dark and pretty early in the severe weather season for Michigan,” said Knox, who was supposed to attend a church event that evening at the school where her father was principal.

“My friend was supposed to play a piano piece, so we were all excited about that. We got to the gym and started eating dinner, and that was when we had the tornado warning. They had just started the program, so my friend never got to play her piano piece because, you know, with a tornado, you don't want to have people in a big open space,” she recalled. “My dad was the principal, so my mom went into the school office, and she said she heard the tornado, you know, the freight train sound. I don't remember hearing it, but the tornado went between the school and our house.”

After the tornado passed, Knox remembers driving home in the dark after the power was knocked out.

“We lost most of the trees in our neighborhood and we didn't have power for a weekend. One of my friends’ garages was picked up, turned 90 degrees and set back down, so the garage door was opening into the yard,” Knox said. “I never thought about going into the weather for a career, but after that, of course I was interested in the weather. And I think it's a very typical story for meteorologists to have a big weather event.”

From physics to forecasts

It wasn’t until she graduated from college that Knox's career path began to drift toward meteorology. She was a physics and math major at Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Michigan, where she grew up, when a moment of self-realization pointed her in a new direction.

“In the first month of college, I was going to do elementary education. Then I started to think about having to deal with all those kids,” she said. “I'm an introvert. And I'm like, ‘I don't think so.’”

The child of math teachers who had a natural ability in the subject, Knox switched her major to a double physics and math major. After earning her bachelor’s degrees, Knox continued on to graduate school, but again decided to switch fields after doing undergraduate physics research.

Knox keeps the state’s Extension agents informed by sharing trends in weather patterns, drought outlooks, climate variability and severe weather events through the Extension weather blog Climate and Agriculture in the Southeast.

Knox keeps the state’s Extension agents informed by sharing trends in weather patterns, drought outlooks, climate variability and severe weather events through the Extension weather blog Climate and Agriculture in the Southeast.

“Physics tends to be really small scale, like atom scale, or really large scale, like universe scale,” she explained. “I wanted to be able to look out the window and understand what was going on. Meteorology was a nice jump. And it's easy to jump from physics into meteorology, because meteorology is a very physical science; you use a lot of math. It's not just going out and forecasting the weather.”

More than just weather

As agricultural climatologist for UGA Cooperative Extension, Knox serves a function much like a broadcast meteorologist but for Georgia’s agricultural producers. She keeps the state’s Extension agents informed by sharing trends in weather patterns, drought outlooks, climate variability and severe weather events through the Extension weather blog Climate and Agriculture in the Southeast.

“For a lot of people, Extension is the only contact they have with the university. That's one of the highest trust relationships that there is.”

“I think they both serve similar purposes — they are the scientists that people relate to,” said Knox, who constantly gathers climate and weather content from sources across the country and around the world to share with agents, producers and blog subscribers.

Knox began her journey to her current role at the University of Wisconsin in Madison where she intended to study satellite meteorology with Verner Suomi, who is considered the father of satellite meteorology, but the professor’s health problems meant much of her master’s studies were done with other scientists. After earning her master’s degree, Knox returned to Calvin College as a replacement teacher for three semesters, teaching classes in physics, astronomy and meteorology. In the summer between semesters, she did an internship in probability of precipitation forecasting with the National Weather Service in Fort Worth, Texas.

“The first night I was there, they had severe weather. I could see supercells with massive clouds hanging all around. It was like 104 degrees (Fahrenheit). Totally cool,” she said. “I went there to study the weather and there it was. You don't usually get that open view of the sky in Michigan.”

Analyzing extreme weather events

After teaching for three semesters, Knox went to work for the National Weather Service in Silver Spring, Maryland, where she spent two years studying data on extremely heavy rain events in the Front Range of the Rockies, including Colorado, the West Coast and the Pacific Northwest.

“They produce statistics on 1-in-100-year storms, only the project I was working in was more like 1-in-a-million-year storms. They have a lot of big dams out west, and those dams have to be built with enough space in the reservoir that, if they get one of these huge storms, it won't overflow, and the dam won't fail. So, when you design a dam out there, you have to know those storm statistics,” she said.

Working with only 50 years of recorded weather data, Knox said determining the probability of a catastrophic weather event involves figuring out what a million-year storm looks like.

“You look at statistics for all the surrounding areas. Even if the storm didn’t hit your watershed, it may have hit a nearby one, allowing you to analyze similarities,” she said. Using computer modeling techniques, meteorologists can run a nearly infinite number of models of a storm by “tweaking” the incoming values of water vapor, temperature, wind direction, topography and more to determine the elements of a worst-case scenario. “I was working mostly on the data, on extreme value theory.” Extreme value theory is used to model the risk of extreme, rare events.

Becoming a science translator

After two years with the National Weather Service, Knox returned to the University of Wisconsin, Madison, to pursue her doctoral degree under pioneering climate scientist John Kutzbach. During her studies, he arranged for her to work two summers at the National Centers for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, on ocean modeling.

While she valued the experience, Knox again realized that the field was not for her. Unsure of what she wanted to do, she was considering teaching high school or adult education when the job of Wisconsin state climatologist became available.

“It was in the same building I was already in, and it involved talking about climate to all different kinds of people. I thought that sounded interesting,” said Knox, who served in the role from 1989 until 1996.

As state climatologist in Wisconsin, Knox began doing the kinds of outreach she is now doing since joining UGA as director of the UGA Weather Network in 2017.

“It was very much a science translator position where you have to understand the science, but you also have to be able to explain it to people who don't. My audience now is mostly Extension specialists, so they're the ones who go out to the farmers with that information because they have the trust relationship, but it is my job to answer the questions they have,” said Knox.

In 1996, Knox and her husband, John Knox, who met while they were both doctoral students at University of Wisconsin, Madison, welcomed their son, Evan. When John graduated in 1996, the family moved to New York City where he worked as a postdoctoral researcher with NASA and Pam did a year-long internship with National Public Radio on its Science Friday program before deciding to become a certified consulting meteorologist.

Bringing climate science to Georgia agriculture

After a 2.5-year stint at Valparaiso University in Northwest Indiana, the Knoxes moved to Athens, Georgia, where Pam Knox took a job as assistant state climatologist for Georgia, working under then-state climatologist David Stooksbury at CAES. John Knox, also a meteorologist, eventually joined the faculty in UGA’s Franklin College of Arts and Sciences, where he now serves as the Josiah Meigs Distinguished Teaching Professor in the Department of Geography and teaches courses in the atmospheric sciences major.

In 2011, after the state climatologist position was moved to the Georgia Environmental Protection Division, Knox began doing grant work with Mark Risse at UGA, looking at how Southeastern crops have been impacted by climate change and on a national project to broaden awareness about climate change through livestock producers and extension educators. When the grant work finished in 2017, Knox was thinking about retiring when she was recruited as director for the UGA Weather Network.

“As Wisconsin state climatologist, I learned a lot about agriculture, and I learned a lot more when I was doing the grant work. I had to learn about how climate and climate variability impacts the growing of different crops, how it impacts cattle and so on, and how that varies across the country,” Knox said.

“Now, every day I'm learning something new about how climate interacts with agriculture.”