CAES entomologist delivers call to action: Create more bee habitat

At TEDxAtlanta, Kris Braman shares insights into the secret life of city bees.

Kris Braman joined the University of Georgia in 1989, researching ways to improve the sustainability and profitability of urban plant production and landscape pest management. The work she's done through the years has not only advanced our scientific understanding of insects, it has informed public policy on issues like pesticide use and environmental protection.

Now leading the Department of Entomology in the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Braman explains that her research takes place at the intersection of pollinator health, ecology and habitat conservation.

Intrigued by her work with urban environments and the pollinators that inhabit them, the organizers of TEDxAtlanta invited Braman to share the results of a recent study she and a team of researchers published on urban bee populations. The TEDx talk, hosted at Georgia State University's Rialto Center for the Arts, contributed to a forum designed to inspire and ignite the curiosity of listeners all over the globe.

In front of a hushed audience, Braman takes a steadying breath. She wears a “Bulldog Red” coat and a shining bumble bee pendant. She smiles, with a characteristic twinkle in her eye, and asks the audience to imagine a world without bees.

Some of you might be happy – no more pests buzzing around and no chance of being stung. And, some of you might simply be unconcerned. But, full disclosure, I have worked with insects for more than 40 years and I am absolutely obsessed with bees.

Bees pollinate dozens of food crops, meaning they do the important work of carrying pollen from one plant to another, making it possible for plants to set seed and produce fruit— think blueberries in Georgia or cranberries in Canada.

Would there still be food without bees? Of course, but we would lose everything that adds color to our plates— from the cantaloupe in Texas to sweet peppers in Spain. Even delicacies like Ecuadorian coffee and chocolate benefit from pollinators. I’m not sure about you, but I need my coffee and chocolate!

Bees are the first domino in the food chain. They help plants survive, and we all know that plants are important because they produce both food and oxygen.

So, for those of you who enjoy eating food and breathing air, I’m here to tell you that our bees are in huge trouble and we need to do something about it — fast!

When most of us think of bees, we think of the iconic honey bee. Although they provide high-quality food like honey, they represent a tiny fraction of the entire species.

In the state of Georgia alone, there are approximately 540 species of bees.

Just for fun, here are a few of my favorite bees.

(Collage by Conor Fair)

Bombus pensylvanicus, the American bumble bee

These bumble bees have stout, hairy, robust bodies, mostly black and yellow. They have the rare capability to thermoregulate — they shiver to produce heat to reach the minimum temperature required for flight.

Apis mellifera, the western or European honey bee

This is perhaps one of the most beloved bees of all and is found on every continent except for Antarctica. These bees communicate the locations of high-quality resources to other members of the colony through a unique form of body language called a “waggle dance.”

Osmia georgica, the mason bee

This solitary bee is aptly named for its habit of constructing cells within cylindrical tubes, such as hollowed-out reeds, where it lays individual eggs sectioned off with mud walls. One of the earliest pollinators in the spring, residents can set up bee houses near their gardens to inhabit these pollinators.

Augochlora pura, the green metallic sweat bee

This flying jewel is a pollinator of more than 40 species of plants. Green metallic sweat bees build nests in rotting wood in forests and residential wood piles. So don't be too hasty during your spring cleanup! Leaving a little extra downed wood can help these and other nesting bees find critical habitat.

So, are cities bad for bees?

Many factors contribute to the decline in the bee population, but the loss of habitat through urbanization is considered a major driver of population loss. It is projected that by the year 2030, urban land cover will be triple what it was in the year 2000. Sounds like more bad news for bees, doesn’t it?

Although the annual economic value of biotic pollinators was reported to be $488 million in Georgia alone, the common perception persists: Cities are bad for bees.

My question is, is this true in every case? Can we do anything, or are we doomed?

I hope to convince you that we can offer bees a better life in the city and that you have a very important role to play in their success.

In our quest to learn how well different bee species are surviving urbanization, my former graduate student Amy Janvier led a research survey in which we explored people’s yards in both urban and suburban cities in Georgia.

Our goals were to count the total number of bees, distinguish between the different types of bees, and relate landscape context — meaning the number of trees nearby, the density of buildings and roads, and the proximity of farms to that bee diversity and abundance.

In the midst of our study, Amy tragically lost her life in a terrible car accident. Despite their grief and the global pandemic, Amy’s mother and aunt loaded their cars with Amy’s bee samples and brought them to us. A small team of students and faculty came together as a community to finish and publish the project in Amy’s honor so that her passion for pollinator conservation would live on.

So, this is a story about bees and community. It is also Amy’s story.

The late Amy Janvier collects pollinators in the suburbs of Athens, Georgia. Her research efforts were instrumental in understanding how bees inhabit urban landscapes. (Photo by Michele Hatcher)

The late Amy Janvier collects pollinators in the suburbs of Athens, Georgia. Her research efforts were instrumental in understanding how bees inhabit urban landscapes. (Photo by Michele Hatcher)

A ground-nesting bee emerges from a hole in bare soil. (Photo by Bodie Pennisi)

A ground-nesting bee emerges from a hole in bare soil. (Photo by Bodie Pennisi)

A native bee digs a nest in a stem. (Photo by Bodie Pennisi)

A native bee digs a nest in a stem. (Photo by Bodie Pennisi)

You may be surprised to learn that we documented more than 110 species in various residential landscapes, like your backyard, for example. We were overwhelmed by the diversity we found.

We found that numerous solitary bees, specialist feeders like squash bees and cavity-dwelling bees, all increased with the increase of development and urbanization. Not only that, many soil-dwelling and social bee species also increased as the amount of remnant forest in the city increased.

Although urbanization does not affect all insects equally, we ultimately concluded that the secret of city bees is trees.

In hindsight, this makes complete sense because, historically, most of the land on the East Coast of the U.S. was heavily forested — and this is where these bees originated.

Trees like the eastern redbud are often overlooked when people think about planting for pollinators. (Photo by Bodie Pennisi)

Trees like the eastern redbud are often overlooked when people think about planting for pollinators. (Photo by Bodie Pennisi)

A cuckoo bee stops on a mountain mint blossom. (Photo by Bodie Pennisi)

A cuckoo bee stops on a mountain mint blossom. (Photo by Bodie Pennisi)

Published in the Journal of Insect Conservation, these findings definitively dispel the common assumption that all cities are bad for all bees.

In areas with mixed land use — think cities interspersed with forested areas — bee diversity actually increases. This shows the enriching effect of more blended landscapes with multiple land-cover types.

Having only forest cover limits bee diversity to forest-dwelling species. But forest patches in combination with other resources preserve forest-dwelling species and a host of other bee species that prefer open spaces.

One of our key findings, I think, was just how many bees there were.

In another recently published article in Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, our team emphasized that as landscapes of the world become increasingly urbanized, there is a growing need to incorporate remnant forests and other pollinator habitats into urban planning.

While urbanization reduces the biodiversity of many taxa, there are ample opportunities to improve habitat quality for many organisms by providing adequate floral and nesting resources right in your yard.

Let’s take a look at bees in their natural habitat.

Does this video frighten you or fascinate you?

Interestingly, the vast majority of wild bees nest in the ground. When the swarm emerges, it creates quite a spectacle. However, very few people witness this event —for the obvious reason — they usually run in the opposite direction of the swarm.

In almost every case, animals and insects are just as afraid of you as you are of them. Most wild bees are docile. They want nectar and pollen, not blood.

Now, let’s say you live in a small space in the city, and you decide you want to protect the pollinators but don’t know where to start.

First things first, it is important to understand that wild bees are very similar to humans in that they need a few basic things to survive — food, water and a place to rear their young.

(Video by Keith Delaplane)

(Video by Keith Delaplane)

Here are five simple things you can do to promote bee diversity and abundance:

1. Tolerate a little messiness in your yard and garden — some of us can already check that box. Be sure that bees have access to water.

2. Consider leaving a bare spot in your yard for ground-nesting bees.

3. When you trim your flowers at the end of the season, leave a few stems so the nesting bees will have a home.

4. Instead of a formal garden, go for a cottage garden with a riot of color all season long.

5. Finally, plant more trees for the bees.

On a global scale, it is critical to consider forest cover for conservation planning in mixed-use landscapes. Forest cover has a particularly strong effect on bee assemblages. Forest bees account for nearly a third of the native bee populations in the Eastern United States.

I am happy to say that over the last few years, the conservation needle has moved slightly in the right direction. We have discovered that the best way to get people involved is for them to have a direct positive experience with plants and bees.

To help stimulate new habitats for pollinators and encourage better management practices, we’ve done a few simple yet effective things:

Raised public awareness

Raised awareness of factors that affect needed pollinators

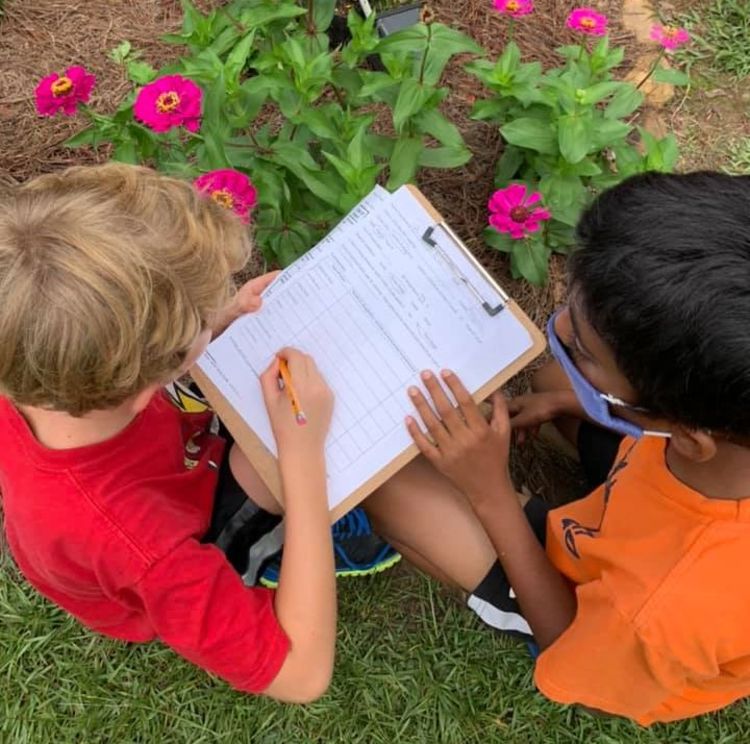

Built school partnerships

Partnered with schools to help enhance their STEM programs

Encouraged local support

Worked with local officials to add pollinator habitats to existing green spaces

The Great Southeast Pollinator Census

In 2017, Becky Griffin, UGA's community and school garden coordinator, designed a statewide citizen-science project to raise awareness of the importance of pollinators and their habitat.

In its fifth year, with a range of public and private partners and support, the project has expanded into North and South Carolina as a regional pollinator census — aptly named the Great Southeast Pollinator Census.

To date, over 20,000 Georgians have participated in the census and more than 2,000 pollinator gardens have been created across more than 100 different counties.

Whether you’re local or you live outside the region, there are so many easy opportunities to get involved. The census, held Aug. 18-19 this year, only takes 15 minutes of your time.

I am completely persuaded that each of you can bee the change that is needed to protect our pollinators and help keep Amy’s dream alive.

I encourage you to bee positive and bee involved. Small changes will lead to huge positive impacts for our bees. Remember, we’re codependent — we need them just as much as they need us!

Leafcutter bees stand on rolled leaves. (Photo by Jena Johnson)

Leafcutter bees stand on rolled leaves. (Photo by Jena Johnson)

I hope that I have convinced you to be pollinator protectors, and remember, the bees are counting on you to get out and spread the buzz!

To learn more about providing plants to sustain pollinators, check out UGA Cooperative Extension Bulletin 1483, “Selecting Trees and Shrubs as Resources for Pollinators.” A recording of Braman's talk is available on YouTube.